ポリコーム群タンパク質

ポリコーム群タンパク質(英: Polycomb-group protein、PcG)は、ショウジョウバエで最初に発見されたタンパク質複合体のファミリーで、遺伝子のエピジェネティックなサイレンシングが起こるようクロマチンリモデリングを行う。ポリコーム群タンパク質は、キイロショウジョウバエDrosophila melanogasterの胚発生時に、クロマチン構造の調節によってHox遺伝子のサイレンシングを行うことがよく知られている。ポリコーム群タンパク質という名称は、このタンパク質の機能の低下の最初の徴候が多くの場合、特徴的な櫛(comb)状の剛毛を持つ前脚へのホメオティックな変換が後脚に生じるものであることに由来する[1]。

昆虫

ショウジョウバエでは、Trithorax群(英語版)(trxG)タンパク質とポリコーム群(PcG)タンパク質は拮抗的に作用し、cellular memory modules(CMM)と呼ばれる染色体エレメントと相互作用する[2]。trxGタンパク質は遺伝子発現を活性化状態に維持し、一方PcGタンパク質は抑制機能によってこの活性化に対抗する。PcGタンパク質は主に3種類のタンパク質複合体、PRC1(英語版)、PRC2、PhoRCに存在する[3]。これらの複合体は共に働き、抑制効果を発揮する。

哺乳類

哺乳類では、PcG遺伝子の発現は、ホメオティック遺伝子の調節やX染色体の不活性化[4]、胚性幹細胞の自己複製[5]など発生段階の多くの面で重要である。X染色体の不活性化においては、PcGは主調節因子であるXIST RNAによって不活性化X染色体へリクルートされる[4]。RINGフィンガー(英語版)PcGタンパク質Bmi1(英語版)は神経幹細胞の自己複製を促進する[6][7]。マウスでのPRC2の遺伝子のヌル変異体は胚性致死であり、PRC1の変異体の大部分はホメオティック変異体として出生し、周産期に致死となる。対照的に、PcGタンパク質の過剰発現はいくつかのがんのタイプで重症度や浸潤性と相関している[8]。哺乳類のPRC1コア複合体はショウジョウバエのものときわめて類似している。Bmi1はINK4遺伝子座(p16Ink4a、p19Arf)を調節することが知られている[6][9]。

Bivalent chromatin部位でのポリコーム群タンパク質の調節はSWI/SNF複合体によって行われ、ATP依存的な除去によってポリコーム複合体の蓄積に対抗する[10]。

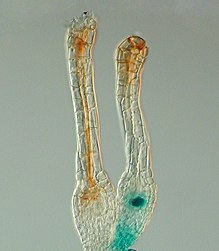

植物

ヒメツリガネゴケPhyscomitrella patensでは、PcGタンパク質FIEは未受精卵細胞などの幹細胞で特異的に発現している。受精の直後、発生中の二倍体の胞子体ではFIE遺伝子は不活性化される[11]。

哺乳類とは異なり、PcGは細胞を未分化状態に維持するために必要である。そのため、PcGの喪失は脱分化を引き起こし、胚発生を促進する[12]。

ポリコーム群タンパク質は、FLC(英語版)(flowering locus C)遺伝子のサイレンシングにより、開花を制御する[13]。この遺伝子は植物の開花を阻害する経路の主要な部分をなし、冬季の間のサイレンシングは植物の春化の主要な因子の1つである[14]。

出典

- ^ Morris KV, ed (2008). “The Role of RNAi and Noncoding RNAs in Polycomb Mediated Control of Gene Expression and Genomic Programming”. RNA and the Regulation of Gene Expression: A Hidden Layer of Complexity. Caister Academic Press. pp. 29–44. ISBN 978-1-904455-25-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=r67Lrf9r9XEC&pg=PA29

- ^ Maurange, Cédric; Paro, Renato (2002-10-15). “A cellular memory module conveys epigenetic inheritance of hedgehog expression during Drosophila wing imaginal disc development”. Genes & Development 16 (20): 2672–2683. doi:10.1101/gad.242702. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 187463. PMID 12381666. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12381666.

- ^ Alhaj Abed, Jumana; Ghotbi, Elnaz; Ye, Piao; Frolov, Alexander; Benes, Judith; Jones, Richard S. (11 27, 2018). “De novo recruitment of Polycomb-group proteins in Drosophila embryos”. Development (Cambridge, England) 145 (23). doi:10.1242/dev.165027. ISSN 1477-9129. PMC 6288389. PMID 30389849. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30389849.

- ^ a b “Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains”. PLOS Genetics 4 (10): e1000242. (October 2008). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000242. PMC 2567431. PMID 18974828. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2567431/.

- ^ Heurtier, V., Owens, N., Gonzalez, I. et al. The molecular logic of Nanog-induced self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Commun 10, 1109 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09041-z

- ^ a b “Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways”. Genes & Development 19 (12): 1432–7. (June 2005). doi:10.1101/gad.1299505. PMC 1151659. PMID 15964994. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1151659/.

- ^ “Bmi1, stem cells, and senescence regulation”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 113 (2): 175–9. (January 2004). doi:10.1172/JCI20800. PMC 311443. PMID 14722607. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC311443/.

- ^ “Polycomb group genes: keeping stem cell activity in balance”. PLOS Biology 6 (4): e113. (April 2008). doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060113. PMC 2689701. PMID 18447587. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2689701/.

- ^ “Epigenetic regulation of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a locus: in sickness and in health” (PDF). Epigenetics 5 (8): 685–90. (2010). doi:10.4161/epi.5.8.12996. PMC 3052884. PMID 20716961. http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/epigenetics/article/12996/?nocache=2141572894.

- ^ “Smarca4 ATPase mutations disrupt direct eviction of PRC1 from chromatin”. Nature Genetics 49 (2): 282–288. (February 2017). doi:10.1038/ng.3735. PMC 5373480. PMID 27941795. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5373480/.

- ^ “Regulation of stem cell maintenance by the Polycomb protein FIE has been conserved during land plant evolution”. Development 136 (14): 2433–44. (July 2009). doi:10.1242/dev.035048. PMID 19542356.

- ^ “CHD3 proteins and polycomb group proteins antagonistically determine cell identity in Arabidopsis”. PLOS Genetics 5 (8): e1000605. (August 2009). doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000605. PMC 2718830. PMID 19680533. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2718830/.

- ^ “Repression of FLOWERING LOCUS C and FLOWERING LOCUS T by the Arabidopsis Polycomb repressive complex 2 components”. PLOS ONE 3 (10): e3404. (2008). Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.3404J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003404. PMC 2561057. PMID 18852898. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2561057/.

- ^ “The molecular basis of vernalization: the central role of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC)”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97 (7): 3753–8. (March 2000). doi:10.1073/pnas.060023597. PMC 16312. PMID 10716723. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC16312/.

関連文献

- “Genome Regulation by Polycomb and Trithorax: 70 Years and Counting”. Cell 171 (1): 34–57. (September 2017). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.002. PMID 28938122. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01596016/file/mmc3%20%281%29.pdf.

- “Transcriptional regulation by Polycomb group proteins”. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 20 (10): 1147–55. (2013). doi:10.1038/nsmb.2669. PMID 24096405.

- “Occupying chromatin: Polycomb mechanisms for getting to genomic targets, stopping transcriptional traffic, and staying put”. Molecular Cell 49 (5): 808–24. (2013). doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.013. PMC 3628831. PMID 23473600. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3628831/.

- “Gene silencing and Polycomb group proteins: an overview of their structure, mechanisms and phylogenetics”. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 17 (6): 283–96. (2013). doi:10.1089/omi.2012.0105. PMC 3662373. PMID 23692361. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3662373/.

- “Polycomb silencing mechanisms and the management of genomic programmes”. Nature Reviews. Genetics 8 (1): 9–22. (January 2007). doi:10.1038/nrg1981. PMID 17173055.

- “Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins”. Cell 128 (4): 735–45. (February 2007). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.009. PMID 17320510.

- “A view of nuclear Polycomb bodies”. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 22 (2): 101–9. (2012). doi:10.1016/j.gde.2011.11.004. PMC 3329586. PMID 22178420. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3329586/.

関連項目

- PRC1(英語版)

- PRC2

外部リンク

- “polycomb group proteins”. Humpath.com. 2020年12月27日閲覧。

- The Polycomb and Trithorax page of the Cavalli lab This page contains useful information on Polycomb and trithorax proteins, in the form of an introduction, links to published reviews, list of Polycomb and trithorax proteins, illustrative power point slides and a link to a genome browser showing the genome-wide distribution of these proteins in Drosophila melanogaster.

- Drosophila Genes in Development: Polycomb-group in the Homeobox Genes DataBase

- Chromatin organization and the Polycomb and Trithorax groups in The Interactive Fly

- polycomb group proteins - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス(英語)